How to Tackle the SAT History/Social Science Reading Passages

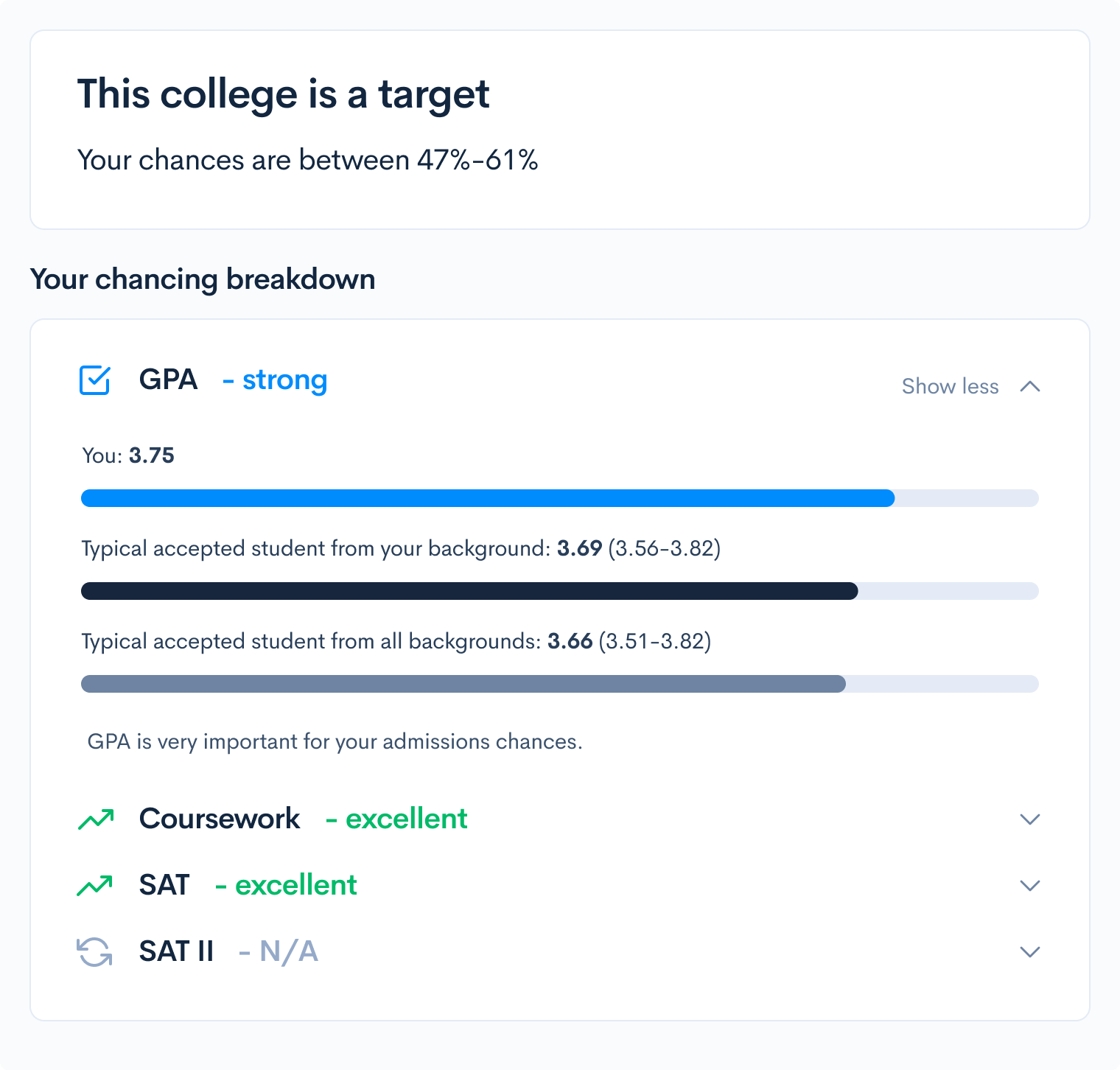

The SAT Reading Test is designed to measure a specific set of reading skills through a wide range of written subject matter. Literary questions gauge your reading comprehension skills, while scientific passages evaluate your data-interpretation abilities. The social studies questions within the reading section of the SAT are your chance to showcase your penchant for finding textual evidence, understanding purpose, analyzing arguments, and more. It won’t be a test of your knowledge of the social sciences, but instead of your skills in understanding them. In this post, we’ll give a brief overview of the SAT social studies reading passages, as well as our best tips and strategies for success. As stated on the Collegeboard website, the SAT reading section includes the following passages: Today, we will be focusing on just the social science and historical passages. These make up the bulk of the reading section, so it’s important to become skilled at them. Though none of these questions involve math, they will test your analytical ability to examine hypotheses, interpret data, and consider the implications of the given information. You might read arguments, speeches, or explanations of studies and experiments in passages ranging from a ninth-grade to first-year college level. Most colleges accept both the ACT or SAT and heavily consider it as a predictor of college success (outside of non-COVID years). In fact, selective schools often use grades and test scores as a filter, so if your academics don’t make the cut, your full application may not even be considered. If you want to know how your SAT score impacts your chances of acceptance to your dream schools, you can check out our free Chancing Engine. It will help predict your odds, compare your profile to that of other applicants, and make suggestions for improving your profile. Unlike other solely stats-based chancing calculators, ours considers many aspects of your profile, including your stats, extracurriculars, and background. Sign up for your free CollegeVine account today to gain access to our Chancing Engine and jumpstart your college journey! Compared to the ACT, the SAT is pretty generous with its allotted time per question, but this comes with one caveat: its questions are often rather in-depth, conceptual, and time-consuming. Therefore, if you frequently run out of time in your practice tests and get bogged down by detail, it’s not because you’re a slow person. Instead, this could be a sign to work on your test-taking time management skills. Here’s a strategy that works for some students: Read the blurb at the beginning of every passage. It usually gives the passage title, author’s name, and perhaps the study or work of literature it was taken from. Many students gloss over it because they see it as an unnecessary footnote, but in reality, the blurb holds crucial bits of information. The author’s name and the excerpt’s origin can provide helpful context surrounding the time period and field of study the passage concerns, while the title may give you some hints about the author’s intent and approach. Read the questions before the passage. There’s no need to read the potential answers, however, as those probably won’t make sense to you just yet. Reading the questions should give you a sense of what to look for when actually reading the passage, and some of them can be done without reading through the whole thing at all! For example, Vocabulary in Context questions (e.g.: “What is the meaning of ‘set’ in this sentence?”) can be answered rather easily by just referring to the passage and reading the sentence before and after the target word. Reading the whole passage is typically not necessary for these, so you can often answer them immediately. Questions based on a graph or chart are similar. Since they often just rely on your ability to interpret visual data, you can often answer these immediately without reading the passage. All questions are worth the same, so you might as well do the easy ones first! Take note of what the questions are looking for. This can include the author’s purpose, intent, objections, points, and more. Take special note of paired questions that may ask you to justify your response to the previous question with textual evidence. Other “solo” questions may ask you to point out textual evidence to support an author’s claim. Finally, go back and read the passage with the questions in mind. Read on for some tips for doing so effectively! Go back and answer the questions, referring back to the passage as needed. These passages can be a little dense and stuffy, so it may be helpful to mentally summarize what the author is saying and infer their intent. Paraphrasing the content will force you to understand it instead of mindlessly glossing over it. As you read, constantly question and consciously process the information. What is the author’s intent? Motive? What are they trying to say? In the margins, note central ideas and key takeaways as you encounter them. Notice the organization of the work and the general flow of ideas from one paragraph to the next. Figure out the author’s thesis, or the central idea they’re trying to communicate. Paragraphs will have their own mini-thesis of sorts, as each was included to explore a mini-idea of its own or fulfill a specific purpose. Finally, when referring back to the passage to find the answer to a question, learn to skim, not reread. By picking up on the general idea of each portion of the passage rather than simply re-reading it, you’ll save yourself time, allowing yourself to read the crucial bits more carefully. Read for meaning, not memorization. While we urge you to read carefully and do your best to retain the information in the short term, it’s also important to not get bogged down by detail. Focus on retaining the core ideas of the passage, not the individual wording. As we mentioned earlier, margin notes can be great tools for organizing your thoughts. You can mark up specific sections mentioned in the questions, write down two-word summaries of each paragraph’s central ideas, and take note of question evidence. Be careful not to spend too much time on this, though; only annotate when it’s necessary for organizing your thoughts! Here are some specific things that may be helpful to note: Keep in mind that this type of annotating isn’t the same as the sort you would do if you were reading a good book. Test-taking annotations are focused and intentional. As we mentioned earlier, each paragraph is carefully chosen and curated by the author to build a coherent explanation or argument. Be aware of counterpoints, transitions, and organization. This will often occur naturally when you practice active reading and annotation. The passage’s structure will differ depending on the type of passage you are reading. Historical ones, for example, may follow a natural sequence of events. Within this format, note cause-and-effect processes, overall trends, and general takeaways, depending on what the questions are looking for. Words like “hence,” “therefore,” and “consequently” can be clear giveaways. The SAT will often pose a pair of passages by different authors discussing a certain topic. Sometimes, the authors will be neutral or even agree, but for the most part, they’ll disagree. A quick tip: if the authors do disagree, you’ll likely be asked what they do agree upon for at least one question, so keep an eye out for that! It’s often a small detail, so you’ll be better off looking for it on your first reading of the passage instead of having to spend extra minutes later on coming back to comb through the passage. For many kids, the social sciences just aren’t all that interesting. Though your eyes may naturally glaze over in economics class, that same mindset won’t work in the classroom. You have to discipline yourself to pay attention to what you’re reading, and this can only be practiced through, well, reading! Proper sleep and nutrition can significantly aid your capacity for attention, but the level of attention you pay is entirely up to you! This goes for reading answer choices, too! Most students miss questions that they are fully capable of answering correctly because they simply didn’t read closely enough. SAT questions often ask for answers that are the “best” or “closest,” which can get tricky. That’s what makes process-of-elimination such a helpful strategy. The moment you realize that an answer choice contains a disqualifying detail or angle, cross it out! This will allow you to narrow your focus on the more plausible answers. While reading historical speeches, internally pretend it is you who is giving the speech to an attentive audience. “Being” the speaker forces you to take note of the emotion, cadence, and crucial details behind the words, keeping you from glossing over important information too quickly. As we mentioned earlier, engagement is crucial, and this tip can boost it! If you want to practice your close reading skills, we recommend reading these books in preparation for the SAT. If you’d like additional practice for certain types of SAT reading questions, Khan Academy offers highly-specific practice sections. For more SAT study tips, check out some of our other articles: The New SAT Reading Test: Strategies for Question Types 15 Hardest SAT Writing and Language Questions How to Tackle the SAT Literary Reading Questions Finally, personalize your own study plan! Think of our suggestions as tips to try out to see if they work for you. What’s Covered:

What Does the SAT Reading Test Cover?

How Will the SAT Impact My College Chances?

Tips and Strategies for the SAT History/Social Science Passages

1. Manage Your Time

2. Practice Active Reading

4. Annotate Wisely

5. Notice Structure

6. Note Opposing Viewpoints

7. Practice Engagement

8. Put Yourself in the Speaker’s Shoes

Final Tips and Resources