Complete Guide to Getting into Medical School

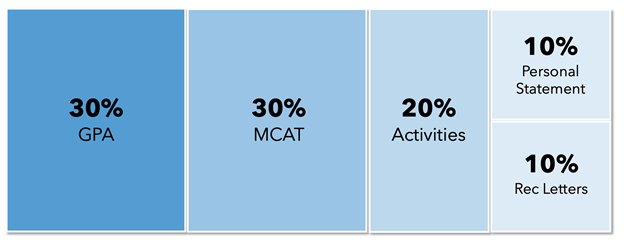

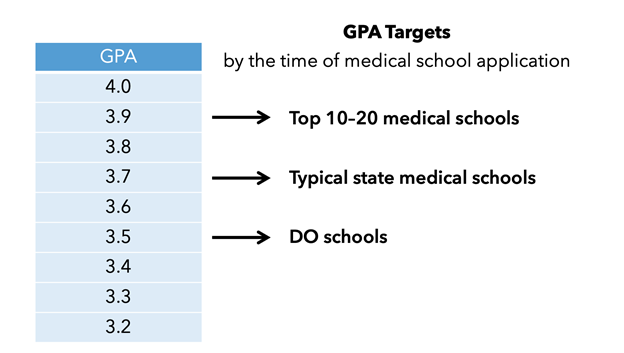

Medical school: It’s a dream for many. Or, at least the end result of becoming a physician is. Unfortunately, it’s a reality for far fewer. Both the path to medical school and the experience itself are extraordinarily demanding. The competition is stiff, and the work is rigorous. That doesn’t mean getting into med school is an insurmountable task. How do you do it? Learn about the process in this in-depth guide. This post covers the pre-med process from freshman year of college and beyond. If you’re in high school, check out our other post: Navigating the Pre-Med Track to Medical School. As you can see, your GPA and MCAT score are the metrics matter the most to admissions committees, constituting 30% of your application each. Meanwhile, activities still carry some weight at 20%, while your personal statement and recommendation letters each count for 10%. Freshman Year The pre-med track starts your first year of college. At that point, you should be meeting with your pre-health advisor, as well as beginning to develop relationships with faculty and mentors — bearing in mind that longer, better-established relationships will result in stronger recommendation letters. (If you have professors teaching large lectures, gain more face-to-face time by attending office hours.) Remember that pre-med is not a major; you can major in anything and go to medical school, as long as you complete the required courses. You should also start thinking about your undergraduate-med school timeline. For example, do you want to begin right after you graduate from undergrad, or will you take a gap year? This is a time to be exploring interests outside of healthcare, too. As you adapt to your coursework, look into joining activities, such as volunteering, research, clubs, paid jobs, and so on. Look into summer positions as well — as with undergraduate admissions, med school adcoms will want to see you spending your time off productively. Later on, you should try to secure leadership roles. Keep in mind that AMCAS activities are measured in hours, so you should start clocking them now. Sophomore Year During your sophomore year, you should work on completing the majority of your pre-med prerequisite courses. This is also the time you should determine whether you’re going to take a gap year, because if you don’t, you’ll need to apply the summer after your junior year. Otherwise, you can wait until after you graduate. Start considering when to take the MCAT. If you’re not taking a gap year, the earliest time to take it is most likely the summer after your sophomore year. You should also be asking professors with whom you’ve developed relationships if they’re willing to write you a recommendation letter — this will prevent awkward situations where you haven’t spoken for a while but still need the letter later on. On the extracurricular side, continue your clinical and non-clinical volunteer and research work, and apply or run for leadership positions within your clubs or organizations. Junior Year April/May This is crunch time. You should take the MCAT if you haven’t done so already. You should also secure your pre-health advising committee letter and order official transcripts from all higher education institutions you’ve attended, including study abroad and summer courses. The AMCAS application becomes available in early May, and you should complete it as early as possible. We also encourage you to start pre-writing your personal statement and activity descriptions. May/June You can submit your AMCAS application in late May or early June. That means you should solidify your school list (although you can always add more schools later) and send AMCAS your official transcripts. Confirm with your recommendation writers that they have submitted their letters. Once you are sure that your primary application is as high quality as possible, submit it. The AAMC will need to verify all of your information, and this process will take several weeks unless you get it in early. Keep in mind that your schools won’t receive your application until it has been verified. After you’ve submitted it, consider pre-writing secondary, school-specific essays. July/August At this point, students who have had their AMCAS applications verified will receive invitations to complete the secondary applications. It’s important to complete them as soon as possible because you will not be considered for an interview invitation until all your materials have been received. Plus, it’s easier to secure an interview at the beginning of the admissions cycle when there are plenty of invitations still available. These invitations will begin to be sent in early August. Senior Year (or Application Year) September–March This is interview season. To prepare, see if your college’s pre-health advising office offers mock interviews. Because almost all schools require in-person, on-campus interviews, you’ll need to balance travel and school commitments. Continue to watch application status websites or Twitter feeds for individual medical schools to know the status of your application. You should also send update letters — after ensuring that the school accepts them — if you’ve had any significant changes, such as new leadership positions, publications, or anything else of note. This can be combined with a letter indicating ongoing interest. October–May October 15th is the earliest date a medical school will notify applicants of an acceptance. Some schools have rolling admissions, which generally begin 4-6 weeks following an interview; most top schools, however, notify students about decisions around the same time in early spring. March–May This is when “Second Look” weekends take place for admitted students to learn more about schools to which they’ve been admitted. May–June By May 15th, accepted students must send their “Intend to enroll” notices that they plan to matriculate at a given medical school. Around this time, final decisions about waitlists are usually made, typically by the end of June. After this period, the school year will begin. Most medical schools start between July and September. Here are the different med school tiers, based on selectivity. We’ll delve into each one more deeply and share how applicant expectations vary. The average MCAT score for medical school admissions is 510 out of 528. Your targets depend on the type of school you’re aiming for, as listed below: You should strive for a score that’s above the 50th percentile for accepted students at your target school. Your pre-med coursework provides a basis for further independent study. Given that the MCAT is an endurance test as much as an assessment of your skills — it takes more than six hours to complete — you’ll need to prepare extensively. Practice exams will likely offer the best preparation, and you should attempt to take them under simulated testing conditions. Types of Prep Materials When you’re preparing, certain materials can help you get ready. For example, you can receive practice tests and information booklets directly from the AAMC and access online materials for free or at a reduced cost via organizations like Khan Academy or Coursera. Courses like Kaplan and Princeton Review are more expensive, around $2,000 for in-person classes and $1,500 for online, self-directed materials. Timelines It’s best to take the MCAT after you’ve completed your pre-med prerequisites since they’ll give you a strong foundation for your independent, self-directed study. Admissions open in May, and the last test is usually in April. It’s a good idea to take the exam on the earlier side to give yourself ample time to retake it — up to 20% of students end up doing so. You should also schedule the test following an extended period of less strenuous activity so you’ll have plenty of time to study (for example, you might take it over a summer where you’re undertaking part-time research). According to our survey, a majority of students spend 20 hours per week studying over three months. Keep in mind that medical schools will see every MCAT score, and multiple low scores will hurt your chances of admission. That’s why you should avoid retaking it, especially more than once. You should also factor in the sky-high cost of $320 (though you may qualify for a fee waiver). Low Test Scores If you receive a low test score, you’ll need to reassess and adjust your expectations. Try to emphasize other strengths in your essays and activity write-ups. You should also consider additional schools, such as osteopathic schools, which are typically less selective. Of course, you can retake the exam — in sum, you can take it up to three times per year. Many people end up taking it twice. However, as we’ve noted, med schools will penalize you the more times you take it; retaking it multiple times suggests that you may not be able to handle the rigors of medical school. Clinical Experience Research Experience Service Roles Leadership Roles Volunteer Experience Teaching Experience Fraternity / Sorority Involvement Sports Involvement Activities Required by Medical School Activities that are typically required by medical schools are as follows: Top 10–20 Medical Schools Clinical Experience Research Experience Service Roles Leadership Roles Volunteer Experience Teaching Experience Typical State Medical School Clinical Experience Service Roles Leadership Roles Volunteer Experience DO / Caribbean School Clinical Experience Service Roles Medical schools encourage applicants to have patient care experience, such as working as a scribe or EMT. While volunteering and shadowing are encouraged, too, they mainly involve observation. Patient care does, however, take significantly more time. Because research experience usually spans several years, you’ll need to carefully consider which lab or team is the right one for you. First, think about whether you’d prefer clinical or non-clinical work. While clinical tends to lead to more frequent publications, non-clinical research in a strong lab can lead to publication in high-impact journals. Also, consider the publication history of the principal investigator. You’ll want a mentor who is established but not close to retirement. To find out more about the mentor, ask for feedback from previous mentees. Another consideration is whether you can receive compensation. One drawback of this, though, is that expectations may rise. COVID, of course, presents challenges to the medical school process, but there are steps you can take to set yourself up for success. In terms of research, for example, you can reach out to mentors to help them finish manuscripts. You can also perform remote tasks, such as working with de-identified data. Another idea is to investigate telemedicine options through your school or an affiliated hospital. You might be able to find videoconferencing opportunities with nursing homes and care facilities, make and donate cloth masks, or find forums to address misinformation related to medicine online. The Medical School Admission Requirements (MSAR) is a database made available by the AAMC. For a $28 annual subscription, you can find detailed information, specific requirements, and admissions statistics for every school, including the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles for MCAT scores and GPAs. This is a good starting point for crafting your list. You can also use it to prepare for interviews, using your knowledge of the schools. Unless you have a special admissions hook, you should aim to have an MCAT score and GPA that are above the 50th percentile for an admitted class. This will give you the best chance of receiving an interview invitation. Adcoms will evaluate your MCAT, GPA, activities, essays, and letters of recommendation, so your academic record will need to be considered in the context of your entire application to understand your relative competitiveness. One way to get a better idea of how you compare is to speak with mentors and pre-med advisors about how students with similar profiles have fared in the past — with the understanding, of course, that every candidate and specific admissions pool is unique. Apply to at least 15-20 schools. You should increase that number if you are not as competitive an applicant. However, the more schools you add to your list, the less time you’ll be able to devote to writing a strong secondary application for each school. You may need to apply to more schools, too, if your state’s public medical schools are highly competitive or the state has few or no public med schools. As part of your preparation, you should familiarize yourself with what specific medical schools look for in applicants. For example, some schools, such as Stanford University, value research the most, while others, like Tulane University, emphasize service. To get a better sense of what schools that interest you highlight, read about their history, mission statements, and student perspectives. Keep application costs in mind too. It costs $40 to send your primary application to each additional school, and secondary applications range from $70-150 apiece. You may qualify for a fee waiver, so be sure to look into the requirements. The AMCAS application is the primary document that you’ll send to all medical schools on your list. It consists of: Once a medical school has reviewed your initial application, they will send you a secondary application to complete. Some schools send these forms to all applicants, while others have a GPA and MCAT cutoff. The application generally consists of essays that address topics ranging from specific medical interests to your dream superpower. Given that prompts haven’t changed much from year to year in the past, you can prepare by prewriting. It’s also possible to recycle secondary essays among schools with similar topics. Make sure you submit this application as soon as possible. As with the AMCAS application, you may request a secondary application fee waiver. The goal of your personal statement is to address your genuine reasons for wanting to pursue medicine. Describe how you’ve prepared for the rigors of medical school, and show your “human side” — avoid coming across as robotic or cynical. One way to help this come through is to incorporate personal anecdotes and stories. Use them to illustrate your careers goals, in terms of fields you’re thinking of entering or abstract values. Tips for writing a strong personal statement: You’ll need at least three faculty recommendation letters, including two from a science (biology, chemistry, or physics) instructor and one from a non-science professor. You’ll also need a pre-med committee letter, which will synthesize all the information about a candidate. It’s important to meet with your advisor or committee early on to ensure that the letter is submitted on time. You may also choose to send optional letters from individuals who can attest to your leadership, work, or volunteering. Although these are not usually required, they can bolster your application. Some schools require physician letters, which you can secure by working as a medical assistant, scribe, or EMT. You can also get one by shadowing a physician. Start networking and developing relationships early, remembering that you’ll need letters from science professors, non-science professors, and, in some cases, physicians. Building relationships with faculty usually involves attending office hours. These are classes you should prioritize, too — you should only ask for recommendations from instructors in classes where you earned an A. Network, but avoid being overly aggressive. You can also ask for application advice — you’ll demonstrate that you care about their opinions. When asking for your letter, be sure to send your recommenders your resume/CV and personal statement to help them learn more about you. This will allow them to incorporate your application themes into their letter. Also, provide key points about your strengths; this makes their job easier. Interview season lasts from August to March. Invitations are extended starting in July, and institutions will give you 1-2 months notice with several dates to choose among. Remember that not all candidates receive invitations, so securing one indicates that the school is seriously considering you for admission. The interview itself is a way to differentiate yourself from other candidates. The importance of the interview depends on the school. For example, Ohio State University accepts more than 70% of interviewees, while New York University accepts around 20% of interviewees. If a school places you on a hold or waitlist for an interview, you can send in supplemental information to bolster your application, including awards you’ve earned. Before your appointment, make sure to familiarize yourself with the location. This will help alleviate your anxiety and decrease your chances of being late. You should make sure to get to the location early either way, at least 15 minutes before the interview in case you encounter any unforeseen issues. Lay out your clothes the night before and read through your application in the days leading up to the interview. Anything you included is fair game — if you’re unable to answer questions about your application, you’ll be calling into question the rest of what you’ve written. One important part of preparation is reading up on current events and issues in medicine. You could be asked about them, and having a well-thought-out, nuanced response will leave a positive impression and help keep the conversation flowing. Thoroughly research the program beforehand by speaking to current students, perusing medical school forums, and reviewing the program’s website. You should also practice with mock interviews. Some pre-med offices offer this service; otherwise, you can ask for help from faculty mentors or peers. Final interview tips In general, interviews last around 30-45 minutes and are conducted with a faculty member, student, or physician. Most schools will have 2-3 different interviews. Types include (but are not limited to): Student interview: This tends to be informal, but you should avoid being overly casual. Be sure to stick to making statements that would not be considered offensive to any particular subgroup. Open-file interview: The interviewer has seen your application and already knows information about you. Closed-file interview: The interviewer has not seen any of your application materials Multiple student interviews: This type involves one interviewer with multiple students. Typically, it emphasizes teamwork and may involve an activity or discussion of an ethical scenario. It will assess your ability to analyze, communicate, and collaborate with others without dominating them. Multiple mini interviews: This involves 6-10 short interview stations. You’ll spend about 10 minutes at each station and will tackle issues like ethical dilemmas, teamwork activities, and traditional interviews. Usually, you’ll have 2-3 minutes to prepare your approach or response. One benefit this format offers is mitigated bias since you’ll be evaluated by several different individuals. You’ll be assessed on your ability to think on your feet and solve a variety of problems. No matter what the format, good interviews flow, and time will pass seamlessly, even if the conversation veers away from the original questions. Below are just some examples of questions you might encounter in an interview: 1. Consider why you are being asked the question. For example, if you’re asked about your weaknesses, be introspective and offer a real weakness — something, perhaps, you’re working on — rather than simply stating a strength masked as a weakness. 2. Try to limit your responses to 90 seconds. Prepare an elevator-style pitch about yourself to avoid rambling. 3. Have specific examples or stories for different types of questions. Anecdotes will help illustrate and humanize your experiences. 4. Take responsibility and strike a positive tone throughout. Keep things upbeat. A positive attitude will come through and make the interviewer(s) feel more positively about you in general. Your interviewer will ask you if you have any questions for them near the end of the interview. Make sure you have a few prepared; not having any will come off as a lack of interest on your part. The best questions are ones you can develop naturally from the conversation, but if you can’t, try the following topics: Consider qualities like the school’s history, curriculum, and areas of focus. Think about how they align with your own interests and goals. For example, perhaps you’re thinking of going into primary care or pursuing a dual-degree program. Reflect on your personal preferences, too: the climate and location, class sizes, curriculum design, and so on. Remember that you’re choosing the institution where you’ll spend four years of your life, and your ultimate happiness will reflect in your academic success. You should make this decision for you — not anyone else. If you’re a high schooler considering medicine, it’s important to pick a college that will support your pre-med dreams. Check out our list of the best schools for pre-meds, and use our free chancing engine to see your chances of acceptance to these schools. Sign up for your free CollegeVine account to get started!Overview of the Medical School Process

Relative Importance of Application Components

Pre-Med Timeline

U.S. Medical School Tiers

Undergraduate Profile

GPA Targets

MCAT Score Targets

MCAT Preparation

Most Important Activities

Patient Care Experience

Choosing Research Experiences

Adapting to COVID-19

Building a List of Schools

MSAR Database by AAMC

Creating a School List

Application Components

AMCAS Components

Secondary Applications

Personal Statement

Recommendation Letters

Network Development

Interviews

Timeline of Interviews

Before the Interview

Interview Preparation

Interview Types

Common Questions

How to Answer Interview Questions

Questions to Ask

Selection Process

Factors to Consider in Final Selection of a School